From Screenland Magazine October 1932

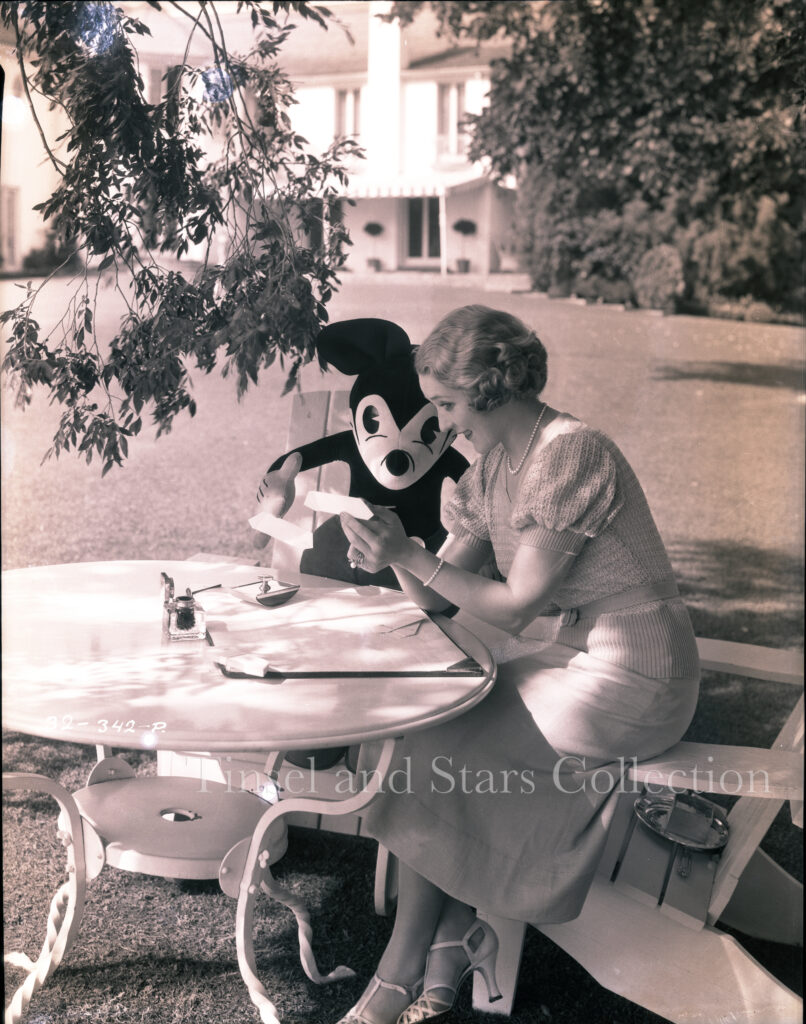

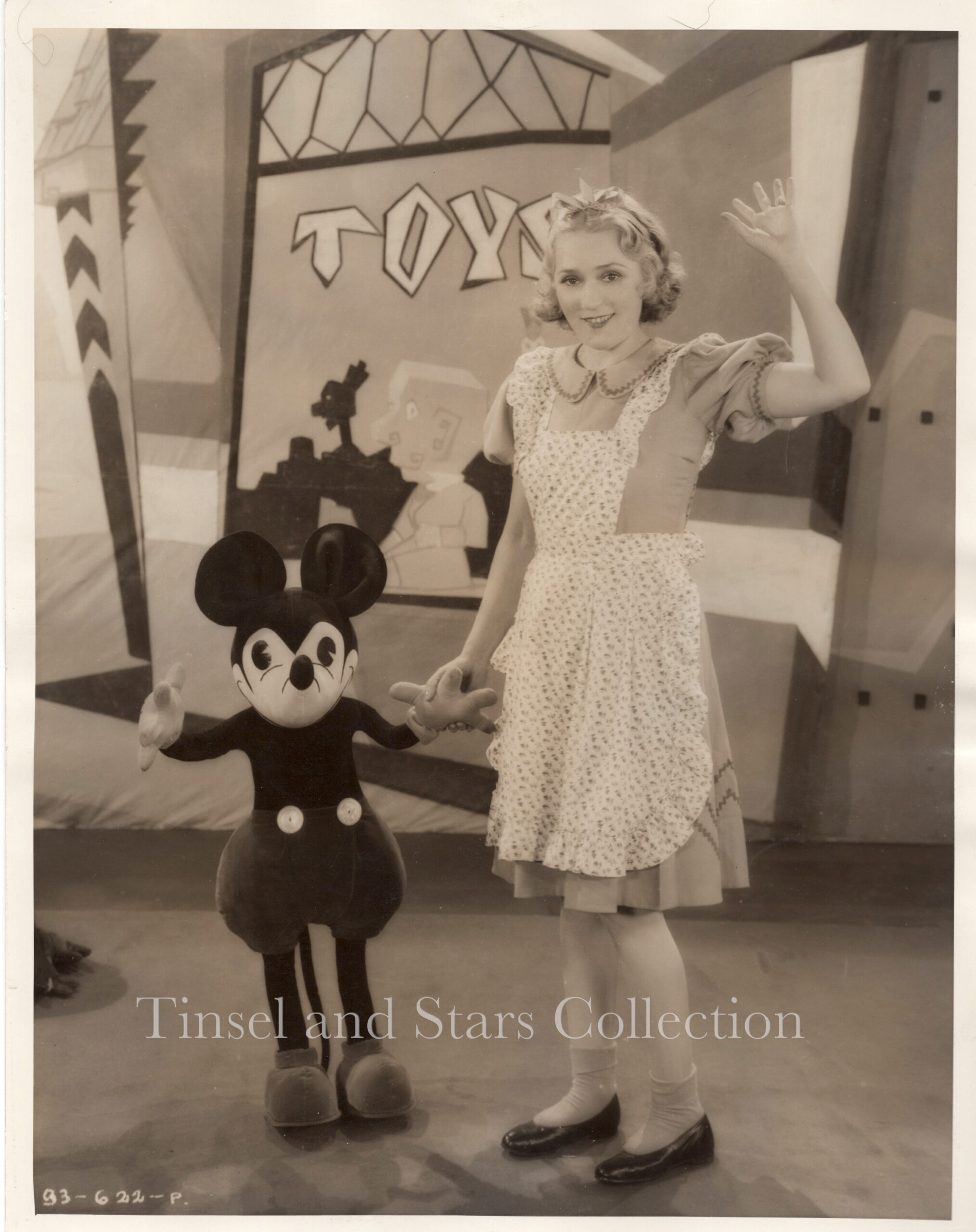

Because Mickey Mouse is Mary Pickford’s favorite movie actor, he went out to Pickfair with me to consult her about a Hallowe’en party.

“But I’ve never had a Hallowe’en party!” protested Mary.

“My little-girl memories of the night are all mixed up with Guy Fawkes’ Day, which is celebrated in Canada on November 5th. You know the old song:

“‘Remember, remember, the Fifth of November!

Gunpowder, treason and plot.

I see no reason

Why gunpowder treason

Should ever be forgot.

Up the ladder, down the hall,

Half a crown will save us all!’

“The two days were so close together and we did the same things for both. We children used to run wildly about the neighborhood, crying: Shell out! Shell out! and the grown-ups would have to come to their doors and give us apples and sweets. Little racketeers, that’s what we were!”

“Then we would reward them by making horrible noises or putting tick-tacks on the windows. Only I never had the courage to do the actual dirty deeds. I played ‘jigger’ for the bobbies—I think you would call it ‘look-out for cops’ here.”

“At home we celebrated with taffy pullings. Poor Mother used to spend days afterwards getting the sticky stuff out of my long curls! I remember what fun it was to try the taffy in cold water to see if it was ready, and how grimy it got from the small dirty hands, but how delicious!”

“Then we used to bob for apples and try to bite fruit hung in doorways. We did something else in which our small noses came out covered with flour, but I can’t seem to remember what it was.”

Mickey, superb in yellow gloves and rose-colored boots, sat making notes while his hostess admired him.

“I’d like to dress up like Mickey,” she confided. “It wouldn’t be much trouble, except for the nose and I might get a piece of cork, paint it black and put it on with stickum. Dear Mickey, he has no chin to speak of. He can’t be a very strong character, can he? I’m afraid my chin makes doubling for him out of the question.”

Her eyes were very big and brown, her curls very soft and gold. In her dainty blue skirt and sweater, with quaint puffed sleeves, she might have been a modern Alice contemplating one of the creatures from a new Wonderland.

“But you want to hear about a Hallowe’en party. When Gwynne was thirteen, Douglas and I let her give one at Pickfair all by herself. We went out, so that the children should feel no restraint. I think that when a child has a party, no one should ever say ‘Don’t.’ “

“I helped Gwynne decorate and we had pumpkins and witches, black cats and sheaves of corn everywhere. Gwynne fixed up a most gruesome-looking ghost in the room where they were to tell ghost stories and when they’d told all the bloodcurdling tales they knew, Gwynne sent them up to the attic, one at a time, and halfway, someone grabbed them! They loved it.”

“But Gwynne is sixteen now and much too old for Hallowe’en.”

“They will grow up, won’t they? I had a letter from Baby Peggy the other day. Have you seen her? You have? How strange she should have grown so tall! She was the tiniest baby. Her father brought her to the studio hanging on his wrist—yes, really, and a little silken leash that could lift her right off the ground. We all fell in love with her.”

“You’d laugh at her letter. She spoke of making a come-back. A come-back at fourteen! She said she had been a good actress ‘as a child’. A dear little letter.”

“Yes, Mickey, I will tell you about that party! If I have one for my picture friends, we won’t wear costumes. Picture people are bored with dressing up. Hollywood has given several masquerades or costume parties, but they are all failures.”

“The non-professional gets a great kick out of pretending for one night to be someone else. He loses all his inhibitions and plays like a child, or flirts to his heart’s content. But to picture people, costumes mean work, no less.”

“I might make a note on my invitations that clothes had better be taffy-proof, because everyone who comes will have to pull taffy. Perhaps we’d better provide teeth-protectors, too, since they are all to bob for apples.”

“Of course, we’ll play ‘Murder’. Charlie Chaplin is a star at that game. You know his funny little face? He pouts his lips out and tries so hard to look innocent, but he’s nearly always the murderer and we convict him. For some reason, I’m always the judge. I don’t want to be the judge, but that’s how it turns out. Douglas is usually prosecuting attorney.”

“The last time we played, a young girl had been shockingly murdered in a belfry. Charlie was organist of the church. The only clues were a hair ribbon and a small trinket; but somehow the keys to the organ lead us to Charlie. These keys were found in a very suspicious spot and though Charlie fought hard he was convicted.”

“Oh, yes, indeed, Mickey, I’m going to decorate for the party! That’s half the fun of it. I would have big pumpkins with lights inside at the gates of Pickfair, and a broomstick at the door—that’s to keep the witches out, you know, and all guests must step over it. But some of the witches will be inside, lurking in dark corners. And we’ll have a skeleton. And black cats for luck. And a ghost, if I have to impersonate it myself!”

Mickey Mouse and Mary went into conference then about menus and place cards and how to word invitations and I left them in the flowering wonderland of Pickfair.

But let me tell you a secret. If Mary could give a Hallowe’en party without publicity, I know what she’d do.

She’d invite all the children in the Juvenile Hall who are under the supervision of the Juvenile Court and make the party a day-long affair, with bathing in the pool and games on the lawns as additional attractions.

Those small prisoners touched the little star’s heart.

“I remember,” she told me, “I sent dolls and vanity cases to them one Christmas—dolls for the younger ones and the cases for the older girls. Some of those older girls are mothers at fifteen! And do you know, nearly all the girls asked the matron if she thought I’d mind if they took the dolls instead of the vanities. Poor little souls starved for the things that belong to childhood!”

“I went to work when I was five. I missed some things, too.”